Meghan Collins Sullivan/NPR

Meghan Collins Sullivan/NPR

Lately, discussions about artificial intelligence seem ubiquitous.

School administrators and teachers worry about students handing in AI-generated papers; writers, translators, and artists worry that AI may supplant them professionally. Science-fiction magazines are grappling with a deluge of AI submissions — though, Clarkesworld editor Neil Clarke told The New York Times, stories written by chatbots are “bad in spectacular ways,” and therefore quite easy to notice and disqualify.

Artificial minds cannot imagine, and fiction that does not engage the imagination doesn’t deserve the name. And though AI can, technically, translate, only a human can read attentively and sensitively enough to genuinely recreate literature — like these three translated works of science and science-minded fiction — in a new language.

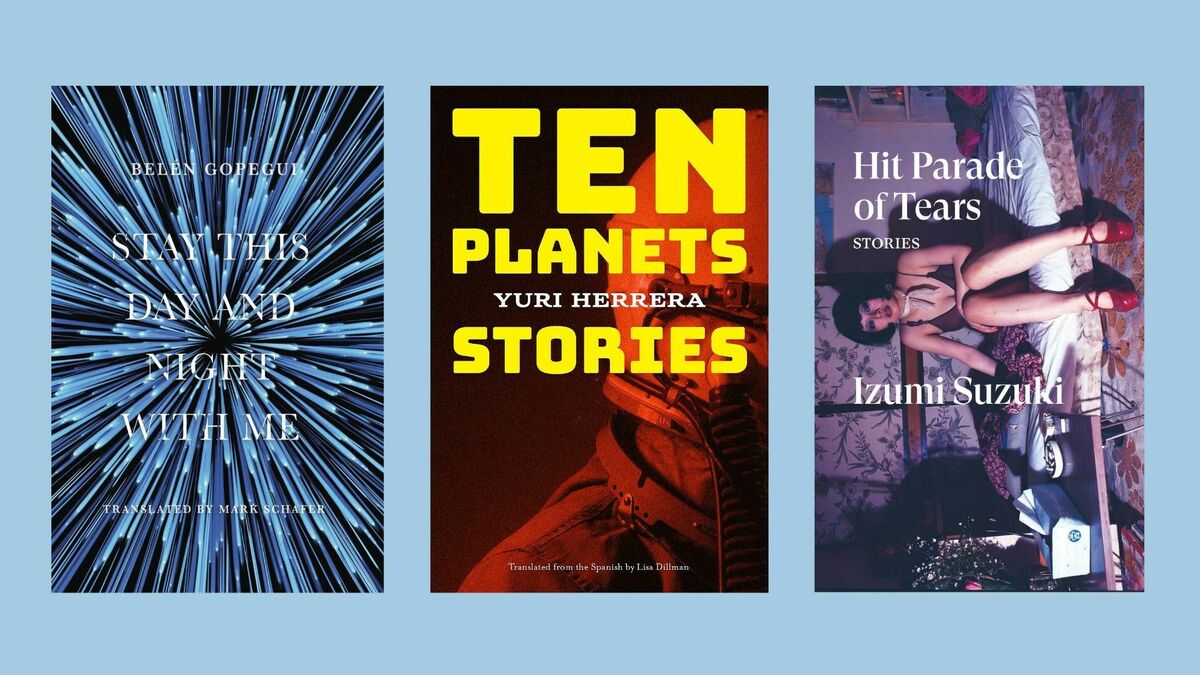

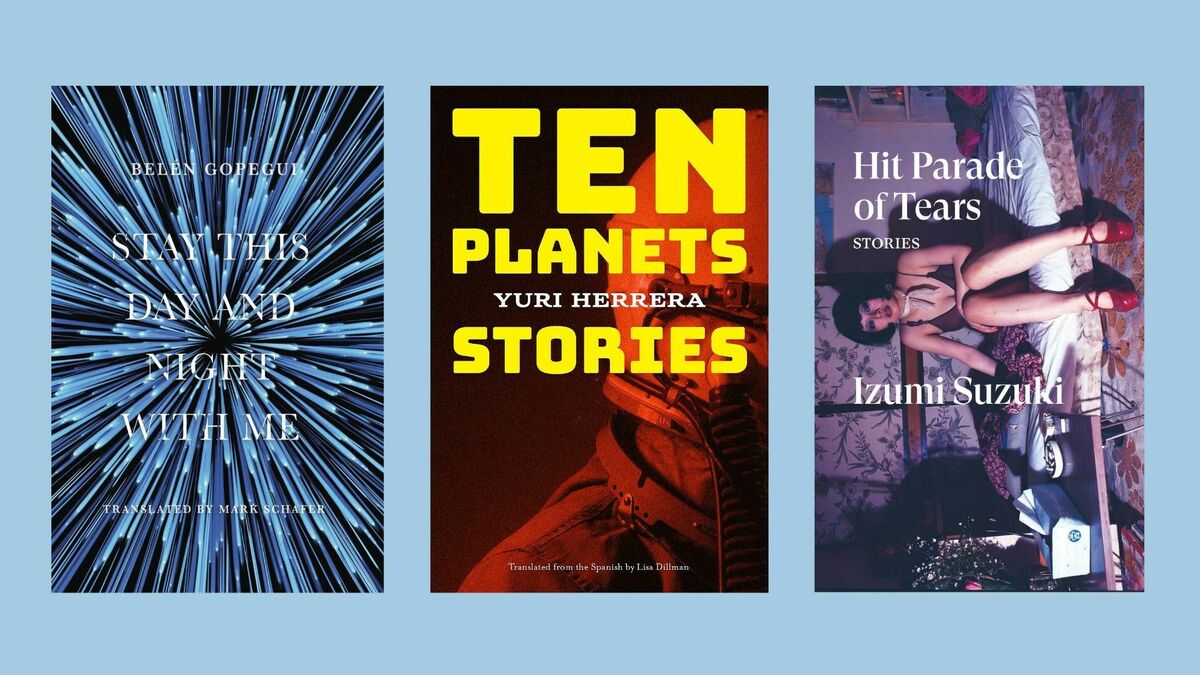

Stay This Day and Night with Me

Belén Gopegui has been one of Spain’s major literary writers since her debut novel, La escala de los mapas, came out in 1993, but her fiction has rarely been translated into English. It’s an oversight translator Mark Schafer is starting to address with Stay This Day and Night with Me, released in Spain in 2017. It isn’t an easy starting point. Stay This Day and Night with Me takes the form of a highly unusual job application sent to Google by a pair of shadowy people named Mateo and Olga. In a brief prologue, a Google HR employee describes the text as a letter that is, “at the same time, …not a letter, it’s a story. And if by story you understand a gymkhana of events, mysteries, and pursuits, then it isn’t a story either.”

Stay This Day and Night with Me has more in common with a Socratic dialogue than a conventional novel. Only at its end does Gopegui motion at rising or falling action. Essentially, the novel consists of Mateo and Olga — the former a student in his early 20s, the latter a mathematician in her 60s — meeting, discovering shared interests in artificial intelligence, robotics, and utopian socialism, and setting out to “engage Google in a serious conversation” about the systemic injustices it enables and perpetrates. Early in the book, Gopegui writes, “Google, you could have worked out how to share your power with people. By doing so you would save them from having to desperately scrape together their own power.” Stay This Day and Night with Me is a portrait of two friends scraping together power, or hoping to, through intellectual exchange. It’s unevenly persuasive, sometimes too abstract, and clumsy in its few gestures at storytelling — but exciting and bracing nonetheless. Gopegui issues an intellectual challenge to Google, and to her readers. What, she asks, do we know that AI cannot — and is it too late to start valuing that knowledge more?

Ten Planets

Yuri Herrera can make anything seem more than real. Signs Preceding the End of the World (2015), the first of his novels to appear in English, turns a young Mexican girl’s voyage across the U.S. border into a mythological epic. The Transmigration of Bodies (2016) and Kingdom Cons (2017) mix contemporary Mexican criminal culture with that of medieval European courts. All three books, translated by Lisa Dillman, bend and reinvent language, adding an element of hyperrealism to his writing even on the sentence level. In Ten Planets, Herrera’s first story collection and his first foray into science fiction, he relies on what the narrator of one of his stories calls “the illusion of precision” to make the unreal — or, at least, the unknowable — seem just as oversaturated as the real worlds he writes so uniquely and well.

Ten Planets‘ stories are linked occasionally and loosely, often by language. (In her afterword, Dillman writes of consciously choosing to string the word iota, one of the many potential translations of the Spanish ápice, through the text.) Many involve voyages to space; in one of the best, “The Martian,” an earthling stranded on an alien planet is moved to “astonishment, intense sorrow, and then uncontainable joy” on encountering a dog. In others, elements of real life — dementia; smartphones — twist into science fiction or grow magical, as in “House Taken Over,” in which a house learns “how to determine what was important,” then forces its inhabitants to live by its moral code. Reading Ten Planets is something like living in that sentient house: More than any of Herrera’s other work, it requires not only suspension of disbelief but surrender of control. Both are challenging; both are worth it. Nobody writes like Yuri Herrera, and it would be a shame not to travel with him as far as his imagination can go.

Hit Parade of Tears

Izumi Suzuki’s science-fiction story collection Hit Parade of Tears, translated from Japanese by Sam Bett, David Boyd, Helen O’Horan, and Daniel Joseph, seems to come from both the past and the future. Suzuki, a model, actress, and writer, was born in 1949 and died by suicide at 36; until 2021, her work had never appeared in English. Hit Parade of Tears, her second collection to be translated, has the could-it-be-prescience that renders good science fiction both captivating and uncanny. At the same time, it often feels so rooted in the ’60s and ’70s that it could have emerged from a time capsule. In “Hey, It’s a Love Psychedelic!,” a story whose protagonists are obsessively interested in the latest clothing and musical trends, a mysterious voice periodically interrupts the narrative to make announcements like, “Warps in the timeline are common.” Suzuki’s work, read in 2023, seems to have fallen out of one such warp.

Hit Parade of Tears‘ best stories are those that speak directly to the troubles of Suzuki’s moment. In the standout “My Guy,” a young woman who delights in the ’60s atmosphere of sexuality, yet has “no interest whatever in sleeping with a man,” is able to open the “innermost reaches of [her] heart” to a visiting alien who makes no sexual demands. In the comical “Trial Witch,” an ill-treated wife uses her newfound magical powers to transform her cheating husband into a side of salmon jerky. Both stories are acidic and spiky, livened equally by their speculative elements and the real anger at their cores. Without the latter, Suzuki’s fiction works less well. Hit Parade of Tears‘ more abstract stories drag; those without a political underpinning often feel underbaked or immature, as do those that, like the crudely shocking “The Walker,” rely too heavily on plot twists. But even when Hit Parade of Tears is missing a layer of sophistication, its prose is strong and clear, a message from the past that has, thanks to her stellar team of translators, arrived here asking to be heard.

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, and critic. Her first novel, Short War, is forthcoming from A Strange Object in 2024.

This story originally appeared on NPR